Federal research funding is changing, with Congress considering a 15% cap on indirect costs—much lower than the usual 40–60% at major universities. In response, the Joint Associations Group (JAG)—a coalition of research and academic organizations—has proposed two FAIR (Fiscal Accountability in Research) models designed to make funding simpler, fairer, and more transparent.

A key shift is the recognition of libraries and scholarly resources as “Essential Research Services” (ERS). This means libraries would no longer be treated as general overhead but as essential parts of research infrastructure, potentially receiving more direct funding.

FAIR Model #1 is a percentage-based system, where essential services like libraries are covered by a fixed rate (e.g., 30%) on top of direct project costs. It is easier to manage but less precise because it uses averages.

FAIR Model #2 is more detailed. It breaks costs into three categories—direct project costs, institution-managed services (including libraries), and general research operations. It gives a clearer view of how research dollars are spent but requires more tracking and setup.

For libraries, this is an opportunity to show their direct impact on research by tracking services like data management, open-access support, and digital repositories. Publishers could also benefit, as these models may create more stable funding for scholarly communication and publishing services.

JAG is seeking feedback to refine these proposals, which could reshape how universities, libraries, and publishers receive funding. You can read more about it here!

Blog

08/12/2025

Will JAG’s New Models Give Libraries and Publishers a Better Seat at the Federal Funding Table?

07/07/2025

Academic Publishing by Day, Trade Publishing by Night (and Lunch)

By Moorea Corrigan, Executive Assistant to Lynne Rienner and Author

I started working at Lynne Rienner Publishers four years ago in May 2021. It was a strange time: I’d graduated from my master’s program in publishing from Simon Fraser University in a digital ceremony in June 2020. Publishing jobs, already thin on the ground, were non-existent with the ongoing pandemic, but a friend of mine in the Denver Publishing Institute sent the opening at Lynne Rienner to me. Lynne and I interviewed via Zoom and the rest is history. I know that I am incredibly lucky to work in publishing, especially in my home state of Colorado.

I started working at Lynne Rienner Publishers four years ago in May 2021. It was a strange time: I’d graduated from my master’s program in publishing from Simon Fraser University in a digital ceremony in June 2020. Publishing jobs, already thin on the ground, were non-existent with the ongoing pandemic, but a friend of mine in the Denver Publishing Institute sent the opening at Lynne Rienner to me. Lynne and I interviewed via Zoom and the rest is history. I know that I am incredibly lucky to work in publishing, especially in my home state of Colorado.

On the other hand, my writing career has only really taken off in the last year and a half. My novel, Thistlemarsh, is due out on April 21, 2026, from Berkley Books in the US, Del Rey in the UK, Harper Italia in Italy, Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial in Spain, Azbooka-Atticus in Russia, and Jangada/Pensamento-Cultrix in Brazil.

I started writing quite young, finishing my first ‘novel’ (it was about fifty pages) when I was in the fifth grade. A micro-press focusing on young authors in Colorado published a YA book I wrote in 2014. However, the publisher got extremely ill, and the publishing house was out of business within the year, making my book out of print before it reached its first birthday. Although this was a fraught process, it kindled my interest in publishing as a career path.

Honestly, nothing could have helped my writing more than living in Edinburgh while I studied for my undergraduate degree in English Literature. Not only did I learn to manage my time to accommodate writing, but the city itself is full of magic and history. I lived (as many of my fellow four-year humanity students did) in Old Town, the medieval side of the city. There, streets cross over each other in layers, labyrinthine and beautiful as they led up to the royal mile. Cafes overlook castles and parks, and clubs populate old smuggling tunnels. New Town is its opposite, with its gorgeous Georgian buildings stretching back to the water in long straight lines. I lived in a Victorian tenement building, and even the mice in our flat felt enchanted to me.

I struggled to find inspiration when I left Edinburgh, but by that time I was firmly in the camp of Stephen King and Elizabeth Gilbert, who champion showing up every day to write, regardless of if inspiration is there or not. My output is nowhere near King’s (insane) 2,000 words a day, but I do write at lunch. I’ve visited all the cafes I can justify in the area around the LRP office. I’ve also found every accommodating picnic table near enough to walk to. There are moments of enchantment in those little places too, from baristas who know my name to the squirrels who scout the benches (and even my purse!) for food as I work.

I am incredibly lucky that I get to spend so much of my life with books, in my day job and in my creative pursuits.

I started working at Lynne Rienner Publishers four years ago in May 2021. It was a strange time: I’d graduated from my master’s program in publishing from Simon Fraser University in a digital ceremony in June 2020. Publishing jobs, already thin on the ground, were non-existent with the ongoing pandemic, but a friend of mine in the Denver Publishing Institute sent the opening at Lynne Rienner to me. Lynne and I interviewed via Zoom and the rest is history. I know that I am incredibly lucky to work in publishing, especially in my home state of Colorado.

I started working at Lynne Rienner Publishers four years ago in May 2021. It was a strange time: I’d graduated from my master’s program in publishing from Simon Fraser University in a digital ceremony in June 2020. Publishing jobs, already thin on the ground, were non-existent with the ongoing pandemic, but a friend of mine in the Denver Publishing Institute sent the opening at Lynne Rienner to me. Lynne and I interviewed via Zoom and the rest is history. I know that I am incredibly lucky to work in publishing, especially in my home state of Colorado.On the other hand, my writing career has only really taken off in the last year and a half. My novel, Thistlemarsh, is due out on April 21, 2026, from Berkley Books in the US, Del Rey in the UK, Harper Italia in Italy, Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial in Spain, Azbooka-Atticus in Russia, and Jangada/Pensamento-Cultrix in Brazil.

I started writing quite young, finishing my first ‘novel’ (it was about fifty pages) when I was in the fifth grade. A micro-press focusing on young authors in Colorado published a YA book I wrote in 2014. However, the publisher got extremely ill, and the publishing house was out of business within the year, making my book out of print before it reached its first birthday. Although this was a fraught process, it kindled my interest in publishing as a career path.

Honestly, nothing could have helped my writing more than living in Edinburgh while I studied for my undergraduate degree in English Literature. Not only did I learn to manage my time to accommodate writing, but the city itself is full of magic and history. I lived (as many of my fellow four-year humanity students did) in Old Town, the medieval side of the city. There, streets cross over each other in layers, labyrinthine and beautiful as they led up to the royal mile. Cafes overlook castles and parks, and clubs populate old smuggling tunnels. New Town is its opposite, with its gorgeous Georgian buildings stretching back to the water in long straight lines. I lived in a Victorian tenement building, and even the mice in our flat felt enchanted to me.

I struggled to find inspiration when I left Edinburgh, but by that time I was firmly in the camp of Stephen King and Elizabeth Gilbert, who champion showing up every day to write, regardless of if inspiration is there or not. My output is nowhere near King’s (insane) 2,000 words a day, but I do write at lunch. I’ve visited all the cafes I can justify in the area around the LRP office. I’ve also found every accommodating picnic table near enough to walk to. There are moments of enchantment in those little places too, from baristas who know my name to the squirrels who scout the benches (and even my purse!) for food as I work.

I am incredibly lucky that I get to spend so much of my life with books, in my day job and in my creative pursuits.

06/10/2025

Course Materials in Higher Education: How Affordable Access Programs Save Students Money and Produce Positive Learning Outcomes

In April of 2025,Tyton Partners released a new, data-driven report on affordable access programs for students in higher education. The report, which presents data from 1,088 colleges and universities in the United States, is the first in-depth analysis of affordable access programs in practice since their inception nearly a decade ago. The findings confirm that course materials are more affordable than they were a decade ago, making them a notable exception to the rising cost of higher education overall.

FINDING #1: Opt-out affordable access models save students money.

Compared to the average digital list price, the average price for opt-out affordable access dropped by 36%, from $91 per class to $58 per class. The report found a total savings of more than $470 million for the students enrolled in affordable access programs at the 1,088 institutions analyzed from 2020-2024.

FINDING #2: Opt-out programs improve student outcomes.

86% of students enrolled in affordable access programs felt better prepared for their courses, and 83% of students indicated that these programs positively impacted their academic success. Peer-reviewed studies show that students are statistically more likely to complete the course and earn a passing letter grade. At one community college, the students were 60% less likely to withdraw from the course and 27% more likely to earn a passing letter grade. The results for some minority students are even greater.

FINDING #3: Institutional stakeholders prefer opt-out and have concerns about the impact of opt-in models on affordability and student outcomes.

Opt-in models require manual enrollment processes that have not worked well in practice and do not guarantee timely access to course materials. Therefore, opt-in models would result in lower participation and a loss of day-one access for a substantial portion of students. Administrators interviewed for the report expressed concern that lower student participation rates in opt-in models would also result in a loss of the cost savings associated with opt-out models. Some institutions cited in the report noted that they would likely stop using affordable access entirely if asked to switch to an opt-in model. They raise particular concerns about first-year and first-generation students.

In conclusion, the Tyton Partners report offers compelling evidence that affordable access programs are delivering on their promise to reduce costs and improve academic outcomes for students in higher education. By leveraging opt-out models, institutions have been able to provide timely, equitable access to course materials while significantly lowering student expenses. The data shows not only dramatic cost savings—over $470 million—but also improved academic performance and engagement, particularly among vulnerable student populations. As the higher education community continues to confront issues of affordability and access, the expansion and support of these programs stand out as a proven, scalable solution that benefits students, institutions, and faculty alike.

FINDING #1: Opt-out affordable access models save students money.

Compared to the average digital list price, the average price for opt-out affordable access dropped by 36%, from $91 per class to $58 per class. The report found a total savings of more than $470 million for the students enrolled in affordable access programs at the 1,088 institutions analyzed from 2020-2024.

FINDING #2: Opt-out programs improve student outcomes.

86% of students enrolled in affordable access programs felt better prepared for their courses, and 83% of students indicated that these programs positively impacted their academic success. Peer-reviewed studies show that students are statistically more likely to complete the course and earn a passing letter grade. At one community college, the students were 60% less likely to withdraw from the course and 27% more likely to earn a passing letter grade. The results for some minority students are even greater.

FINDING #3: Institutional stakeholders prefer opt-out and have concerns about the impact of opt-in models on affordability and student outcomes.

Opt-in models require manual enrollment processes that have not worked well in practice and do not guarantee timely access to course materials. Therefore, opt-in models would result in lower participation and a loss of day-one access for a substantial portion of students. Administrators interviewed for the report expressed concern that lower student participation rates in opt-in models would also result in a loss of the cost savings associated with opt-out models. Some institutions cited in the report noted that they would likely stop using affordable access entirely if asked to switch to an opt-in model. They raise particular concerns about first-year and first-generation students.

In conclusion, the Tyton Partners report offers compelling evidence that affordable access programs are delivering on their promise to reduce costs and improve academic outcomes for students in higher education. By leveraging opt-out models, institutions have been able to provide timely, equitable access to course materials while significantly lowering student expenses. The data shows not only dramatic cost savings—over $470 million—but also improved academic performance and engagement, particularly among vulnerable student populations. As the higher education community continues to confront issues of affordability and access, the expansion and support of these programs stand out as a proven, scalable solution that benefits students, institutions, and faculty alike.

05/05/2025

Does Religion Strengthen Democracy?

By Matthew R. Miles

In an era of political vitriol, democratic backsliding, and increasing partisan violence, researchers and policymakers are scrambling to understand what factors might help strengthen our increasingly fragile democratic institutions. My new book, The Metrics of Faith: Rethinking Religion’s Role in US Politics (Fall 2025), turns conventional wisdom on its head by suggesting an unexpected source of democratic resilience: religious development.

In The Metrics of Faith, I introduce the concept of “religious becoming”—the degree to which individuals develop specific virtues like transcendence (connection to something larger), temperance (self-control and moderation), justice (fairness and ethical behavior), and humanity (compassion and universal love) through their religious engagement. Unlike traditional measures of religion, which focus on doctrinal beliefs or practices, religious becoming examines what people actually become through their spiritual development.

Beyond Church Attendance and Belief

For decades, social scientists have primarily measured religion through three dimensions: belief (theological doctrines), belonging (institutional affiliation), and behavior (practices like prayer and church attendance). These traditional measures often show troubling correlations between religion and concerning political attitudes.

I offer a fundamentally different approach. Rather than focusing on the inputs of religious life, I examine the outputs—the moral and ethical transformation that occurs through religious practice, regardless of specific tradition. This shift in measurement reveals surprising patterns that challenge our assumptions about religion’s role in public life.

Four Counterintuitive Findings

Among my book's most striking revelations:

1. Younger generations are as religious as older ones. They just practice differently. While conventional metrics suggest declining religiosity among Gen Z and Millennials, my religious becoming scale shows these generations have developed the virtues associated with religious maturity at levels comparable to Baby Boomers and the Silent Generation.

2. Religious development predicts political tolerance better than education. For fifty years, political scientists have identified education as the primary driver of tolerance. My research reveals that religious becoming is approximately four times more powerful than education in predicting political tolerance, offering a new perspective on the relationship between these variables.

3. Religious development reduces political sectarianism as strongly as partisan identity increases it. While partisan identities motivate Americans to view opponents as morally corrupt enemies, religious becoming counteracts this toxic form of polarization with almost equal strength in the opposite direction.

4. Religious development works across traditions. The transformative effects of religious becoming is not limited to Christians. Buddhists, Jews, Muslims, and even those identifying as “spiritual but not religious” show comparable levels of religious development despite scoring lower on traditional religiosity measures.

Rethinking Religion's Role in Democracy

These findings suggest we have been telling the wrong story about religion in American public life. Far from being primarily a source of division, authentic religious development may be one of our most valuable resources for strengthening democratic resilience.

When we focus on what religion helps people become rather than just what they believe or practice, we discover that religious development fosters exactly the civic virtues necessary for democracy’s survival. Individuals who score high in religious becoming are significantly more likely to reject political violence, uphold democratic norms, and extend civil liberties even to groups they strongly disagree with.

This doesn't mean all religious expression strengthens democracy. My book distinguishes between forms of religious identity that become intertwined with partisan politics and the deeper spiritual development that transcends political boundaries.

Implications for Our Democratic Future

In a time marked by escalating polarization and democratic decay, my research provides a vital counternarrative. It powerfully suggests that authentic religious development is, in fact, a key to cultivating the virtues our democracy desperately needs.

For religious communities, the findings highlight the importance of focusing on character transformation rather than merely doctrinal conformity or institutional loyalty. For policymakers and civil society organizations, they suggest that dismissing religion’s role would be misguided.

The Metrics of Faith challenges readers to move beyond simplistic narratives about religion’s decline or divisiveness and instead recognize how certain forms of religious development might help us navigate the challenges facing American democracy in the twenty-first century.

In an era of political vitriol, democratic backsliding, and increasing partisan violence, researchers and policymakers are scrambling to understand what factors might help strengthen our increasingly fragile democratic institutions. My new book, The Metrics of Faith: Rethinking Religion’s Role in US Politics (Fall 2025), turns conventional wisdom on its head by suggesting an unexpected source of democratic resilience: religious development.

In The Metrics of Faith, I introduce the concept of “religious becoming”—the degree to which individuals develop specific virtues like transcendence (connection to something larger), temperance (self-control and moderation), justice (fairness and ethical behavior), and humanity (compassion and universal love) through their religious engagement. Unlike traditional measures of religion, which focus on doctrinal beliefs or practices, religious becoming examines what people actually become through their spiritual development.

Beyond Church Attendance and Belief

For decades, social scientists have primarily measured religion through three dimensions: belief (theological doctrines), belonging (institutional affiliation), and behavior (practices like prayer and church attendance). These traditional measures often show troubling correlations between religion and concerning political attitudes.

I offer a fundamentally different approach. Rather than focusing on the inputs of religious life, I examine the outputs—the moral and ethical transformation that occurs through religious practice, regardless of specific tradition. This shift in measurement reveals surprising patterns that challenge our assumptions about religion’s role in public life.

Four Counterintuitive Findings

Among my book's most striking revelations:

1. Younger generations are as religious as older ones. They just practice differently. While conventional metrics suggest declining religiosity among Gen Z and Millennials, my religious becoming scale shows these generations have developed the virtues associated with religious maturity at levels comparable to Baby Boomers and the Silent Generation.

2. Religious development predicts political tolerance better than education. For fifty years, political scientists have identified education as the primary driver of tolerance. My research reveals that religious becoming is approximately four times more powerful than education in predicting political tolerance, offering a new perspective on the relationship between these variables.

3. Religious development reduces political sectarianism as strongly as partisan identity increases it. While partisan identities motivate Americans to view opponents as morally corrupt enemies, religious becoming counteracts this toxic form of polarization with almost equal strength in the opposite direction.

4. Religious development works across traditions. The transformative effects of religious becoming is not limited to Christians. Buddhists, Jews, Muslims, and even those identifying as “spiritual but not religious” show comparable levels of religious development despite scoring lower on traditional religiosity measures.

Rethinking Religion's Role in Democracy

These findings suggest we have been telling the wrong story about religion in American public life. Far from being primarily a source of division, authentic religious development may be one of our most valuable resources for strengthening democratic resilience.

When we focus on what religion helps people become rather than just what they believe or practice, we discover that religious development fosters exactly the civic virtues necessary for democracy’s survival. Individuals who score high in religious becoming are significantly more likely to reject political violence, uphold democratic norms, and extend civil liberties even to groups they strongly disagree with.

This doesn't mean all religious expression strengthens democracy. My book distinguishes between forms of religious identity that become intertwined with partisan politics and the deeper spiritual development that transcends political boundaries.

Implications for Our Democratic Future

In a time marked by escalating polarization and democratic decay, my research provides a vital counternarrative. It powerfully suggests that authentic religious development is, in fact, a key to cultivating the virtues our democracy desperately needs.

For religious communities, the findings highlight the importance of focusing on character transformation rather than merely doctrinal conformity or institutional loyalty. For policymakers and civil society organizations, they suggest that dismissing religion’s role would be misguided.

The Metrics of Faith challenges readers to move beyond simplistic narratives about religion’s decline or divisiveness and instead recognize how certain forms of religious development might help us navigate the challenges facing American democracy in the twenty-first century.

04/14/2025

Building the US Politics List at Lynne Rienner Publishers

By Bill Finan, Senior Acquisitions Editor

Over the years I have looked with more than just a bit of envy at the nearly constant gaggle of people who congregate at the Lynne Rienner Publishers book exhibit booths at ISA or APSA. The animated yet genial conversations have always made me think that the interactions between authors and LRP editors and staff were not the usual conference booth “just the facts” business interactions. There was a personal connection, a sincere interest in the books being discussed—those elements that make the publishing process work so much more smoothly and productively. Now that I am part of LRP as a senior acquiring editor in US politics and public policy, no more envying from afar: the interest, the enthusiasm, and the personal touch are in fact very much what it is to publish with LRP.

Over the years I have looked with more than just a bit of envy at the nearly constant gaggle of people who congregate at the Lynne Rienner Publishers book exhibit booths at ISA or APSA. The animated yet genial conversations have always made me think that the interactions between authors and LRP editors and staff were not the usual conference booth “just the facts” business interactions. There was a personal connection, a sincere interest in the books being discussed—those elements that make the publishing process work so much more smoothly and productively. Now that I am part of LRP as a senior acquiring editor in US politics and public policy, no more envying from afar: the interest, the enthusiasm, and the personal touch are in fact very much what it is to publish with LRP.

Throughout my career, my goal has been to attract and publish important scholarly voices; my work at Lynne Rienner allows me to continue with this focus. My editorial approach is collaborative and hands-on; I believe the best books emerge from a genuine partnership between author and editor. Having worked with a range of authors, I've found that this kind of collaborative editorial guidance can help scholars translate complex ideas into persuasive and accessible narratives without sacrificing intellectual depth.

What am I looking for in potential projects? Work that offers new insights and perspectives on contemporary political challenges. The best academic work, in my experience, combines rigorous scholarship with clear writing that can inform broader public discourse. As the editor of Current History, as an editor at the University of Pennsylvania Press, and then as director of Brookings Institution Press, I have tried to acquire articles and books that have scholarly significance and, when possible, public impact.

For scholars considering submitting a proposal, I am open to nearly all areas of US politics, but am especially interested in topics like the administrative state, the power of the executive, how Congress works, and religion and politics. The best author queries clearly articulate both the scholarly contribution and why the work matters now. US politics is at a challenging moment, and innovative scholarship has never been more important.

I welcome the opportunity to discuss your project ideas and look forward to building a list that contributes to our understanding of the US political landscape. And as I noted at the beginning, publishing is, at its heart, about relationships; I value the process of working with authors to shape and refine their ideas into books that make a difference.

Over the years I have looked with more than just a bit of envy at the nearly constant gaggle of people who congregate at the Lynne Rienner Publishers book exhibit booths at ISA or APSA. The animated yet genial conversations have always made me think that the interactions between authors and LRP editors and staff were not the usual conference booth “just the facts” business interactions. There was a personal connection, a sincere interest in the books being discussed—those elements that make the publishing process work so much more smoothly and productively. Now that I am part of LRP as a senior acquiring editor in US politics and public policy, no more envying from afar: the interest, the enthusiasm, and the personal touch are in fact very much what it is to publish with LRP.

Over the years I have looked with more than just a bit of envy at the nearly constant gaggle of people who congregate at the Lynne Rienner Publishers book exhibit booths at ISA or APSA. The animated yet genial conversations have always made me think that the interactions between authors and LRP editors and staff were not the usual conference booth “just the facts” business interactions. There was a personal connection, a sincere interest in the books being discussed—those elements that make the publishing process work so much more smoothly and productively. Now that I am part of LRP as a senior acquiring editor in US politics and public policy, no more envying from afar: the interest, the enthusiasm, and the personal touch are in fact very much what it is to publish with LRP.Throughout my career, my goal has been to attract and publish important scholarly voices; my work at Lynne Rienner allows me to continue with this focus. My editorial approach is collaborative and hands-on; I believe the best books emerge from a genuine partnership between author and editor. Having worked with a range of authors, I've found that this kind of collaborative editorial guidance can help scholars translate complex ideas into persuasive and accessible narratives without sacrificing intellectual depth.

What am I looking for in potential projects? Work that offers new insights and perspectives on contemporary political challenges. The best academic work, in my experience, combines rigorous scholarship with clear writing that can inform broader public discourse. As the editor of Current History, as an editor at the University of Pennsylvania Press, and then as director of Brookings Institution Press, I have tried to acquire articles and books that have scholarly significance and, when possible, public impact.

For scholars considering submitting a proposal, I am open to nearly all areas of US politics, but am especially interested in topics like the administrative state, the power of the executive, how Congress works, and religion and politics. The best author queries clearly articulate both the scholarly contribution and why the work matters now. US politics is at a challenging moment, and innovative scholarship has never been more important.

I welcome the opportunity to discuss your project ideas and look forward to building a list that contributes to our understanding of the US political landscape. And as I noted at the beginning, publishing is, at its heart, about relationships; I value the process of working with authors to shape and refine their ideas into books that make a difference.

03/06/2025

Why Don’t Most Radicals Commit Acts of Terrorism? A Conversation with Morten Bøås

Posted by Meg Gamble, LRP's Marketing Coordinator

What separates a radical from a terrorist? In the latest episode of An Intelligent Look at Terrorism, host Phil Gurski welcomes Morten Bøås, author of Resisting Radicalization: Exploring the Nonoccurrence of Violent Extremism.

Dr. Bøås brings his extensive research on insurgent groups and political violence to the discussion, offering a nuanced perspective on why most individuals who adopt radical beliefs never actually commit acts of terrorism. He explores the social, economic, and psychological factors at play, challenging simplistic narratives about radicalization and shedding light on the complexities of extremist pathways.

Tune in now here!

An Intelligent Look at Terrorism is a podcast hosted by former Canadian intelligence analyst Phil Gurski, offering expert analysis on terrorism, extremism, and security issues. Through interviews with leading researchers, practitioners, and policymakers, the podcast provides in-depth discussions that move beyond the headlines to explore the real-world complexities of terrorism and counterterrorism.

What separates a radical from a terrorist? In the latest episode of An Intelligent Look at Terrorism, host Phil Gurski welcomes Morten Bøås, author of Resisting Radicalization: Exploring the Nonoccurrence of Violent Extremism.

Dr. Bøås brings his extensive research on insurgent groups and political violence to the discussion, offering a nuanced perspective on why most individuals who adopt radical beliefs never actually commit acts of terrorism. He explores the social, economic, and psychological factors at play, challenging simplistic narratives about radicalization and shedding light on the complexities of extremist pathways.

Tune in now here!

An Intelligent Look at Terrorism is a podcast hosted by former Canadian intelligence analyst Phil Gurski, offering expert analysis on terrorism, extremism, and security issues. Through interviews with leading researchers, practitioners, and policymakers, the podcast provides in-depth discussions that move beyond the headlines to explore the real-world complexities of terrorism and counterterrorism.

02/03/2025

Dr. Justin Quinn Olmstead on GCTV with Bill Miller

Posted by Meg Gamble, LRP's Marketing Coordinator

Dr. Justin Quinn Olmstead, a historian at Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, New Mexico, discusses the lab's pivotal role in advancing global security and technological innovation in this interview from Global Connections Television. His book, From Nuclear Weapons to Global Security: 75 Years of Research and Development at Sandia National Laboratories, discusses the lab's evolution from its origins in nuclear deterrence to its wider contributions to national and international security.

Originally founded as an engineering center for nuclear research, Sandia Laboratories was launched by figures such as Dr. Robert Oppenheimer and President Harry Truman. President Dwight D. Eisenhower later founded the Plowshare Program, which explored peaceful applications of nuclear energy, and Atoms for Peace in 1957, which promoted global nuclear collaboration.

Sandia's work extends beyond nuclear research. Their work has helped address major global challenges such as the BP Oil Spill, the Fukushima nuclear disaster, the Challenger explosion, the 9/11 attacks, and the climate crisis. The lab continues to innovate in areas such as physics, bioscience, and chemical engineering, solidifying its status as a critical institution in global security and scientific advancement.

Check out the video below!

Dr. Justin Quinn Olmstead, a historian at Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, New Mexico, discusses the lab's pivotal role in advancing global security and technological innovation in this interview from Global Connections Television. His book, From Nuclear Weapons to Global Security: 75 Years of Research and Development at Sandia National Laboratories, discusses the lab's evolution from its origins in nuclear deterrence to its wider contributions to national and international security.

Originally founded as an engineering center for nuclear research, Sandia Laboratories was launched by figures such as Dr. Robert Oppenheimer and President Harry Truman. President Dwight D. Eisenhower later founded the Plowshare Program, which explored peaceful applications of nuclear energy, and Atoms for Peace in 1957, which promoted global nuclear collaboration.

Sandia's work extends beyond nuclear research. Their work has helped address major global challenges such as the BP Oil Spill, the Fukushima nuclear disaster, the Challenger explosion, the 9/11 attacks, and the climate crisis. The lab continues to innovate in areas such as physics, bioscience, and chemical engineering, solidifying its status as a critical institution in global security and scientific advancement.

Check out the video below!

01/06/2025

Women in Publishing: A Special Discussion

Posted by Meg Gamble, LRP's Marketing Coordinator

As the founder and publisher of Lynne Rienner Publishers, Lynne has not only built a successful independent publishing house but also has carved a path for women in an industry that once offered them limited opportunities.

During an event hosted last year to commemorate Women’s History Month, led by early-career professionals from Emerson College, Lynne joined a panel of distinguished women to discuss their journeys and impact on academic publishing. The panelists shared their experiences as trailblazers, reflecting on the challenges they faced in establishing their businesses and their commitment to publishing groundbreaking work that amplifies diverse voices.

The discussion touched on the hurdles women have historically faced in publishing, the importance of innovation, and how to survive in an ever-evolving industry. Lynne’s dedication to independence and quality has made her a role model for aspiring publishers and a champion for women’s advancement in the field.

The event concluded with a Q&A session, where Lynne offered candid advice and encouragement to students and young professionals looking to follow in her footsteps. Her story exemplifies how resilience, vision, and a willingness to break the mold can lead to meaningful change.

Check out the video below!

As the founder and publisher of Lynne Rienner Publishers, Lynne has not only built a successful independent publishing house but also has carved a path for women in an industry that once offered them limited opportunities.

During an event hosted last year to commemorate Women’s History Month, led by early-career professionals from Emerson College, Lynne joined a panel of distinguished women to discuss their journeys and impact on academic publishing. The panelists shared their experiences as trailblazers, reflecting on the challenges they faced in establishing their businesses and their commitment to publishing groundbreaking work that amplifies diverse voices.

The discussion touched on the hurdles women have historically faced in publishing, the importance of innovation, and how to survive in an ever-evolving industry. Lynne’s dedication to independence and quality has made her a role model for aspiring publishers and a champion for women’s advancement in the field.

The event concluded with a Q&A session, where Lynne offered candid advice and encouragement to students and young professionals looking to follow in her footsteps. Her story exemplifies how resilience, vision, and a willingness to break the mold can lead to meaningful change.

Check out the video below!

12/05/2024

Transforming to Adapt to Climate Change by John Barkdull

John Barkdull is author of the recently published, Confronting Climate Change: From Mitigation to Adaptation

As temperatures rise even further, adaptation could demand profound alteration of social, economic and political institutions. Transformational adaptation in a radically changed world could be required to cope with massive human migration, profound changes to agricultural practices, severe stress on infrastructure and human habitation, health threats, and more.

The most recent two major IPCC reports assert that rising temperatures could require transformational adaptation rather than such incremental adaptations as strengthening infrastructure and installing air conditioning. Numerous policy makers and scholars have adopted the language of transformation to signal the urgency of the climate crisis, including the Secretary-General of the United Nations.

The pressing question might become whether existing global and national institutions are capable of identifying, selecting, and implementing the drastic measures that a hot world will require. It may be that a growth-oriented global economy in a world order dominated by heavily armed sovereign states simply cannot recognize, choose, or implement effective, humane forms of adaptation. If adaptation demands reallocation of resources away from current priorities such as military spending, maximizing profits, and consumerism, then a global capitalistic state system could stand as the major obstacle to meeting the climate challenge. If so, then transformation must encompass profound change in global and national economic, political, social, and cultural institutions. Thus, transformation would mean much more than the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy. Transformation would mean radical social change, probably to ecosocialism.

Although the IPCC has asserted the importance of transformational responses to climate change, and many officials and scholars have made the same plea, the fact is that high-level negotiations proceed as if existing institutions are largely unalterable, and that they are capable of managing the problem.

But if existing institutions prove unable to meet the challenge, then the world could experience chaotic, poorly planned, inequitable and even violent responses to the social disruptions resulting from climate change. Accordingly, leaders in the UN, other important international organizations, national governments, and citizens must take seriously the full scope of what adaptation might require for civilization to survive and thrive.

The study I conducted showed that adaptation has been part of the global dialogue on climate change since the world first paid attention to the problem. Over the decades, adaptation became understood to require profound institutional transformation. But official negotiators have not embraced the full implications of transformation. Possibly, as the effects of climate change become more obvious and more damaging, transformational adaptation of economic and political institutions will be on the global agenda. The world can only hope that it is not too late.

This year, August became the fifteenth straight month of record high global temperatures. We are seeing the consequences now. For example, Phoenix, Arizona experienced 113 consecutive days of temperatures over 100ºF, smashing the previous record of 76 days in 1993. Hospitals reported patients suffered serious burns from touching hot surfaces such as pavement. In late September 2024, Hurricane Helene struck the US Southeast, resulting in over 200 fatalities and nearly $100 billion in damages. Broadly, societies have endured scorching heat waves, destructive hurricanes, devastating floods, and unprecedented species loss on every continent.

The resulting higher temperatures mean societies and communities must adapt to a much warmer global climate, and even more adaptation will be required in the future. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the UN body charged with informing policymakers of the most recent climate science, states that adaptation is about “reducing climate risks and vulnerability,” and it asserts adaptation should enable “climate resilient development.” Adaptation entails a process of adjustment to changing climatic conditions to reduce the damage to the ecology and to human society. International negotiations, scholarship, and science have increased their emphasis on adaptation as global average temperatures have risen and prospects for meeting emissions reduction goals have dimmed.As temperatures rise even further, adaptation could demand profound alteration of social, economic and political institutions. Transformational adaptation in a radically changed world could be required to cope with massive human migration, profound changes to agricultural practices, severe stress on infrastructure and human habitation, health threats, and more.

The most recent two major IPCC reports assert that rising temperatures could require transformational adaptation rather than such incremental adaptations as strengthening infrastructure and installing air conditioning. Numerous policy makers and scholars have adopted the language of transformation to signal the urgency of the climate crisis, including the Secretary-General of the United Nations.

The pressing question might become whether existing global and national institutions are capable of identifying, selecting, and implementing the drastic measures that a hot world will require. It may be that a growth-oriented global economy in a world order dominated by heavily armed sovereign states simply cannot recognize, choose, or implement effective, humane forms of adaptation. If adaptation demands reallocation of resources away from current priorities such as military spending, maximizing profits, and consumerism, then a global capitalistic state system could stand as the major obstacle to meeting the climate challenge. If so, then transformation must encompass profound change in global and national economic, political, social, and cultural institutions. Thus, transformation would mean much more than the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy. Transformation would mean radical social change, probably to ecosocialism.

Although the IPCC has asserted the importance of transformational responses to climate change, and many officials and scholars have made the same plea, the fact is that high-level negotiations proceed as if existing institutions are largely unalterable, and that they are capable of managing the problem.

But if existing institutions prove unable to meet the challenge, then the world could experience chaotic, poorly planned, inequitable and even violent responses to the social disruptions resulting from climate change. Accordingly, leaders in the UN, other important international organizations, national governments, and citizens must take seriously the full scope of what adaptation might require for civilization to survive and thrive.

The study I conducted showed that adaptation has been part of the global dialogue on climate change since the world first paid attention to the problem. Over the decades, adaptation became understood to require profound institutional transformation. But official negotiators have not embraced the full implications of transformation. Possibly, as the effects of climate change become more obvious and more damaging, transformational adaptation of economic and political institutions will be on the global agenda. The world can only hope that it is not too late.

11/04/2024

It's time to CELEBRATE . . .

LRP just turned 40 … and we couldn’t have done it without the support and encouragement of countless friends and colleagues! We are sending out a huge thank you to all!

In celebration, we welcome you to our redesigned website. Our new platform will, we hope, not only enhance your experience, but also foster a deeper connection with our community of scholars, librarians, educators, and other readers.

Over the years, we’ve strived to be a pioneering force in independent publishing, and we take great pride in what and who we publish. We’re honored by the relationships we’ve formed along the way. What follows are some kind words from just a few of our spectacular authors.

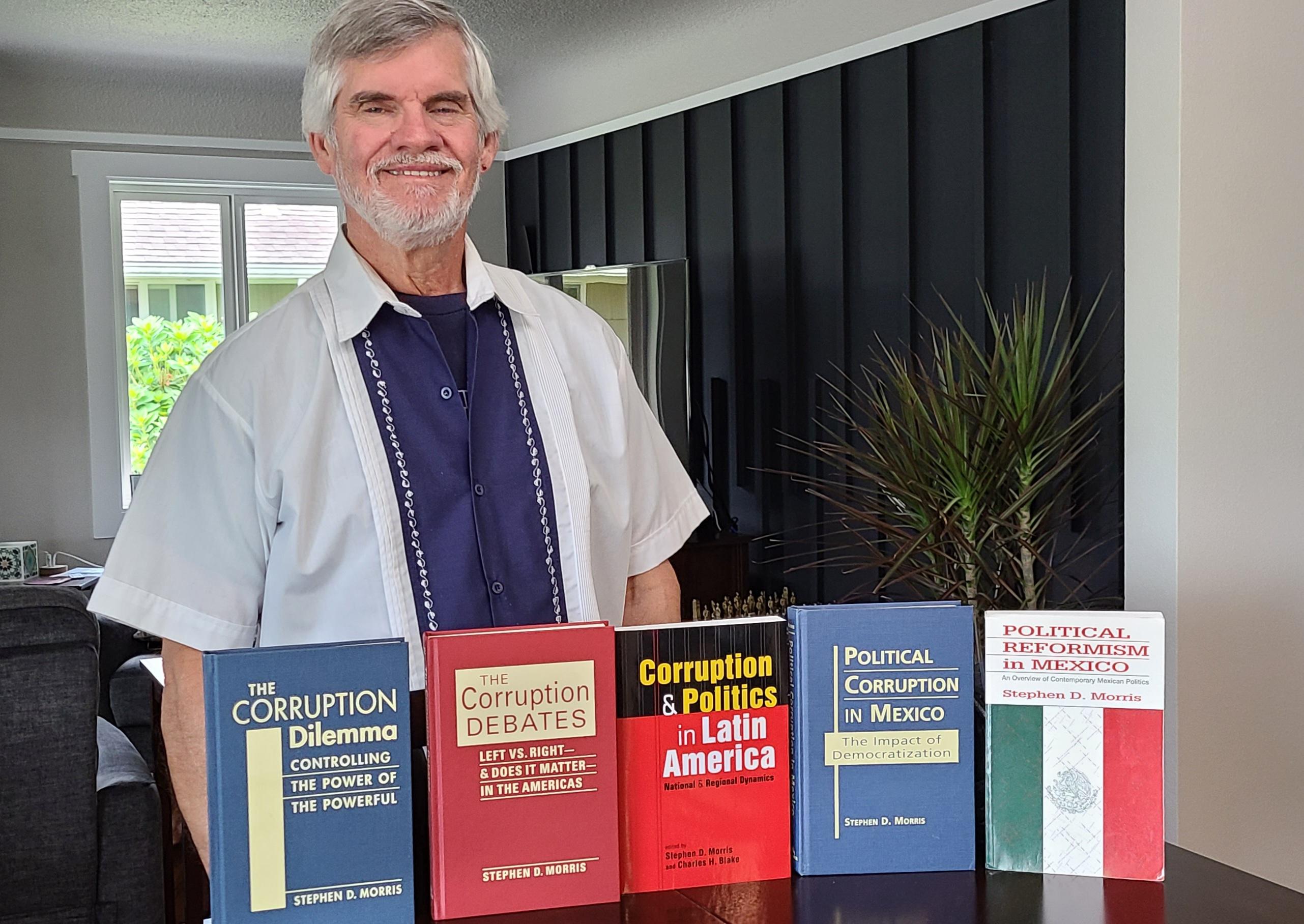

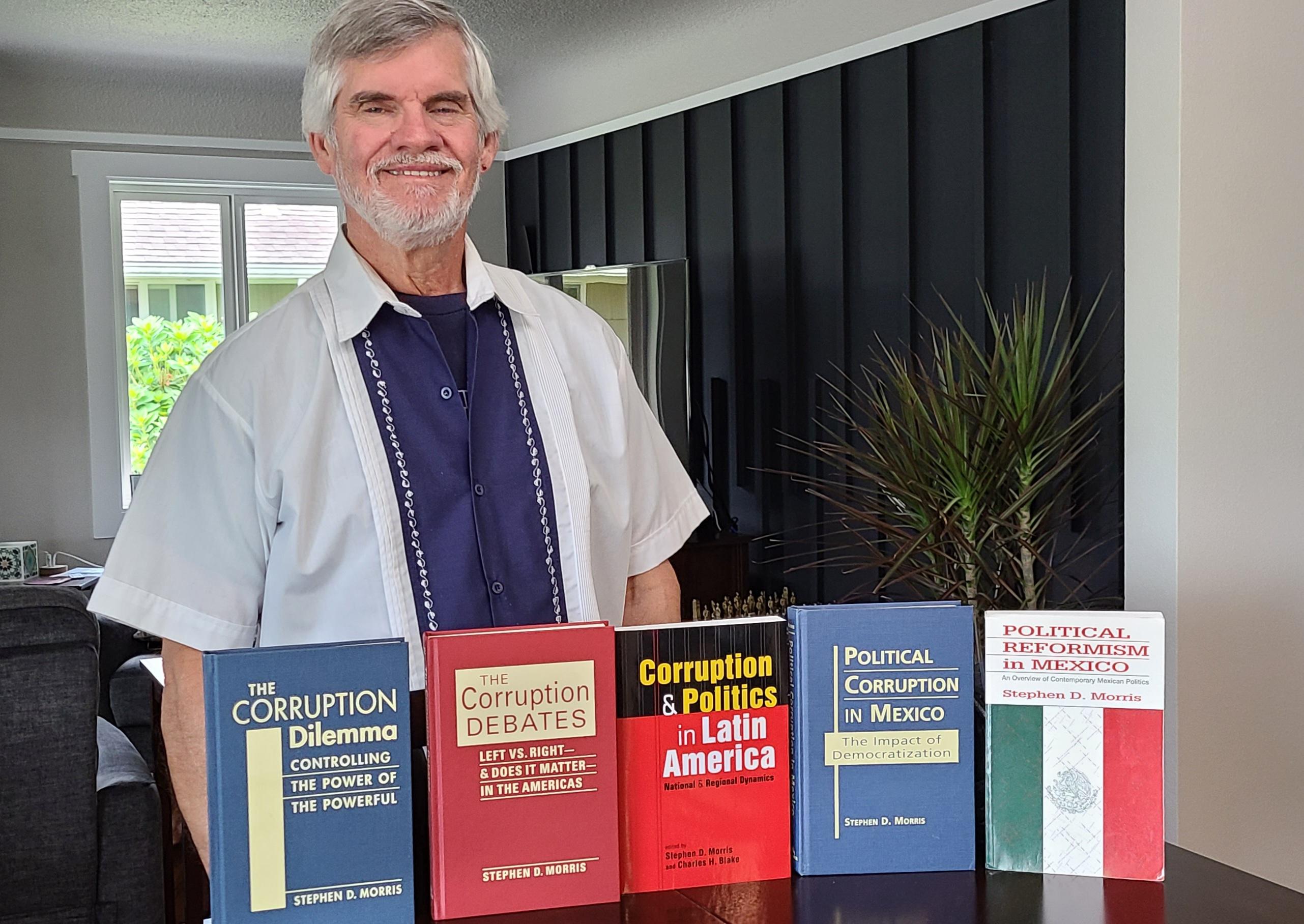

Stephen Morris, author of The Corruption Dilemma: Controlling the Power of the Powerful and many more:

I have had the pleasure of working with Lynne and her team for many years. They couple kindness with professionalism, making the publishing experience pain-free and fulfilling. Congratulations on 40 years of contributing to intellectual explorations and discoveries.

John Clark, editor of Political Identity and African Foreign Policies and coauthor of Africa’s International Relations: Balancing Domestic and Global Interests:

Lynne Rienner has been a great friend to the scholarly community that studies the Global South. She takes a personal interest in every project, and LRP publishes the highest quality work in the social sciences. Lynne’s eye for excellence and innovation in academic work is unmatched. Her deep understanding of the social science world has helped countless scholars, myself included, improve their work. The LRP staff refines and processes manuscripts with great professionalism, but in a timely manner. The publications of LRP have been a great resource for the scholarly community for over forty years.

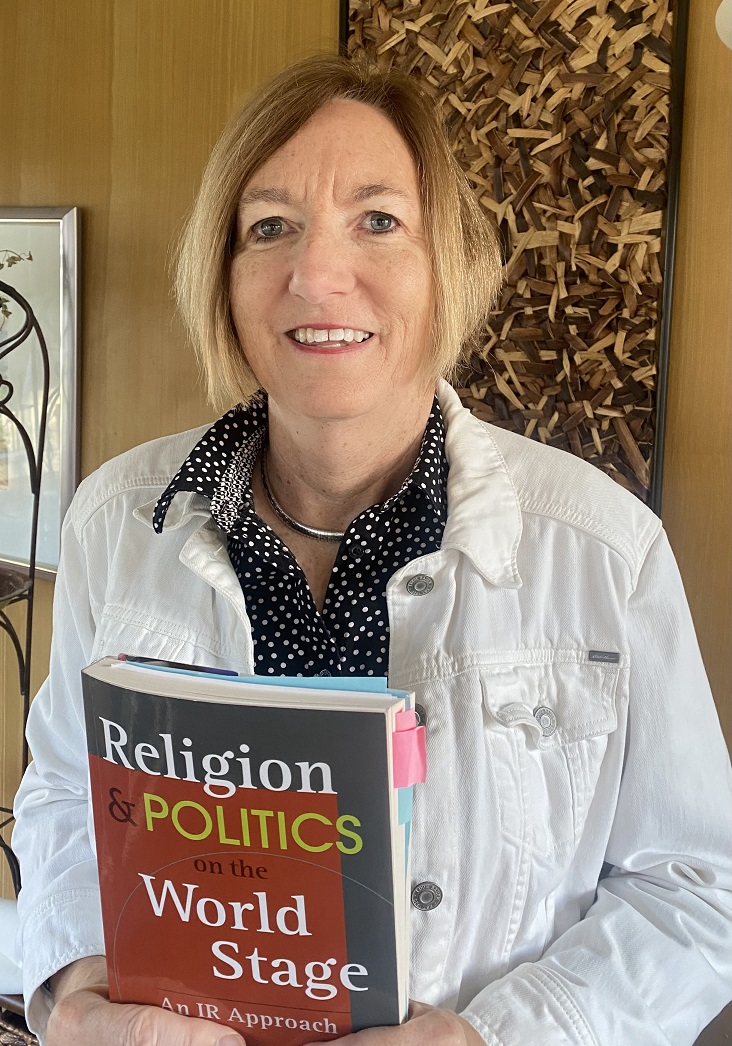

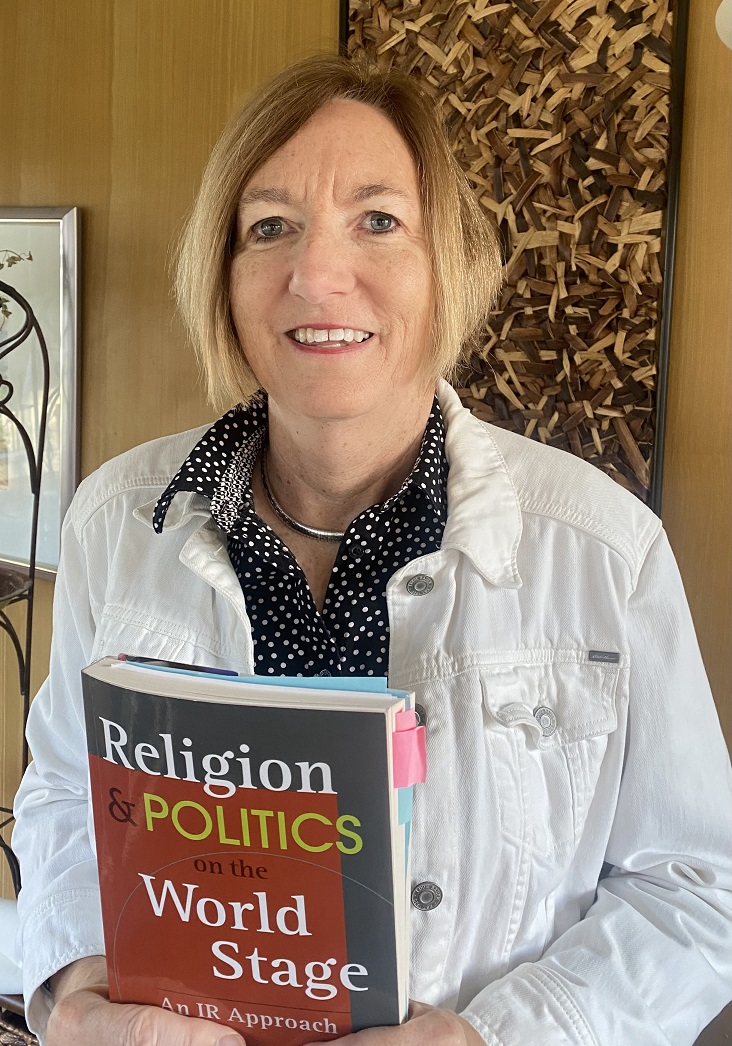

Lynda Barrow, author of Religion and Politics on the World Stage: An IR Approach:

Writing during summers and sabbaticals, Religion and Politics on the World Stage was a nine-year labor of love. I was thrilled to have LRP publish it - and to work with Lynne Rienner directly as the editor. Her guidance resulted in a better, more focused book.

Robert Springborg, editor of Security Assistance in the Middle East: Challenges ... and the Need for Change among others:

I may hold LRP's record for author and editor with most books published under its imprint. The first was in 1999 followed in 2021 and 2023 with hopes for two more in 2025.

I have obviously been a glutton for the pleasure of working with what I have found to be the most dedicated, professional, considerate publisher in the business, headed and staffed by folks with whom it is always a delight to deal and whose personal engagement with publishing projects is unequalled. This happy state of affairs is due both to the commitment of Lynne and her staff, and to the fact that theirs is one of the few remaining entirely independent, privately owned presses. How nice it is to be able to join LRP's outstanding list of publications on the Middle East.

I should like to raise a toast to Lynne and her staff for their signal contribution to academic publishing while making the experience of doing so such a pleasurable one for me and for friends and colleagues.

In celebration, we welcome you to our redesigned website. Our new platform will, we hope, not only enhance your experience, but also foster a deeper connection with our community of scholars, librarians, educators, and other readers.

Over the years, we’ve strived to be a pioneering force in independent publishing, and we take great pride in what and who we publish. We’re honored by the relationships we’ve formed along the way. What follows are some kind words from just a few of our spectacular authors.

Stephen Morris, author of The Corruption Dilemma: Controlling the Power of the Powerful and many more:

I have had the pleasure of working with Lynne and her team for many years. They couple kindness with professionalism, making the publishing experience pain-free and fulfilling. Congratulations on 40 years of contributing to intellectual explorations and discoveries.

John Clark, editor of Political Identity and African Foreign Policies and coauthor of Africa’s International Relations: Balancing Domestic and Global Interests:

Lynne Rienner has been a great friend to the scholarly community that studies the Global South. She takes a personal interest in every project, and LRP publishes the highest quality work in the social sciences. Lynne’s eye for excellence and innovation in academic work is unmatched. Her deep understanding of the social science world has helped countless scholars, myself included, improve their work. The LRP staff refines and processes manuscripts with great professionalism, but in a timely manner. The publications of LRP have been a great resource for the scholarly community for over forty years.

Lynda Barrow, author of Religion and Politics on the World Stage: An IR Approach:

Writing during summers and sabbaticals, Religion and Politics on the World Stage was a nine-year labor of love. I was thrilled to have LRP publish it - and to work with Lynne Rienner directly as the editor. Her guidance resulted in a better, more focused book.

Robert Springborg, editor of Security Assistance in the Middle East: Challenges ... and the Need for Change among others:

I may hold LRP's record for author and editor with most books published under its imprint. The first was in 1999 followed in 2021 and 2023 with hopes for two more in 2025.

I have obviously been a glutton for the pleasure of working with what I have found to be the most dedicated, professional, considerate publisher in the business, headed and staffed by folks with whom it is always a delight to deal and whose personal engagement with publishing projects is unequalled. This happy state of affairs is due both to the commitment of Lynne and her staff, and to the fact that theirs is one of the few remaining entirely independent, privately owned presses. How nice it is to be able to join LRP's outstanding list of publications on the Middle East.

I should like to raise a toast to Lynne and her staff for their signal contribution to academic publishing while making the experience of doing so such a pleasurable one for me and for friends and colleagues.